Volumetric Supernova Rates with ZTF

2024-Present; Northwestern; Advisor: Prof. Adam Miller

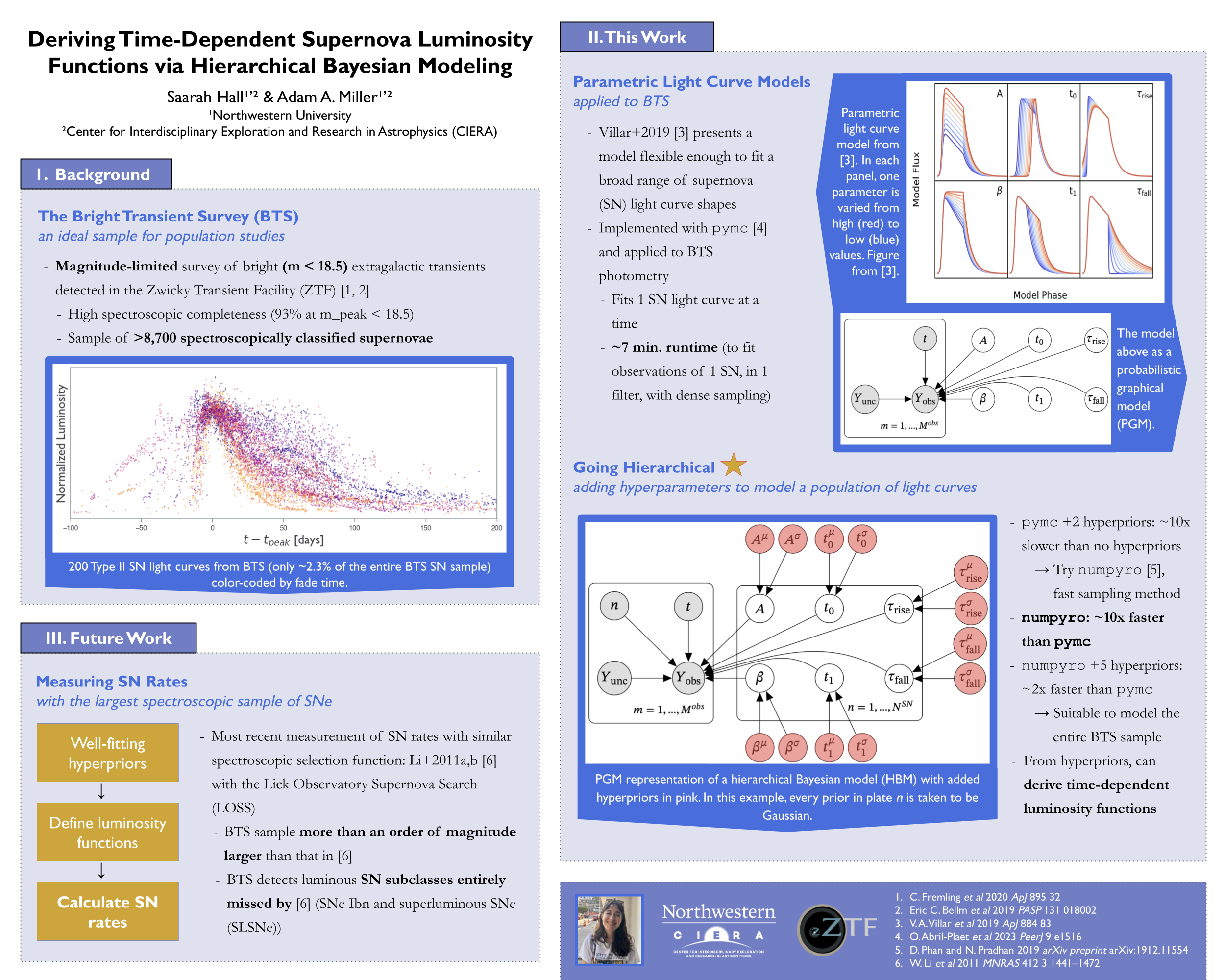

Description coming soon! While you wait, here is a poster I presented at the Rise_Time conference at Purdue:

Data Reduction Pipeline for SEDMv2

2022-2024; Northwestern; Advisor: Prof. Adam Miller

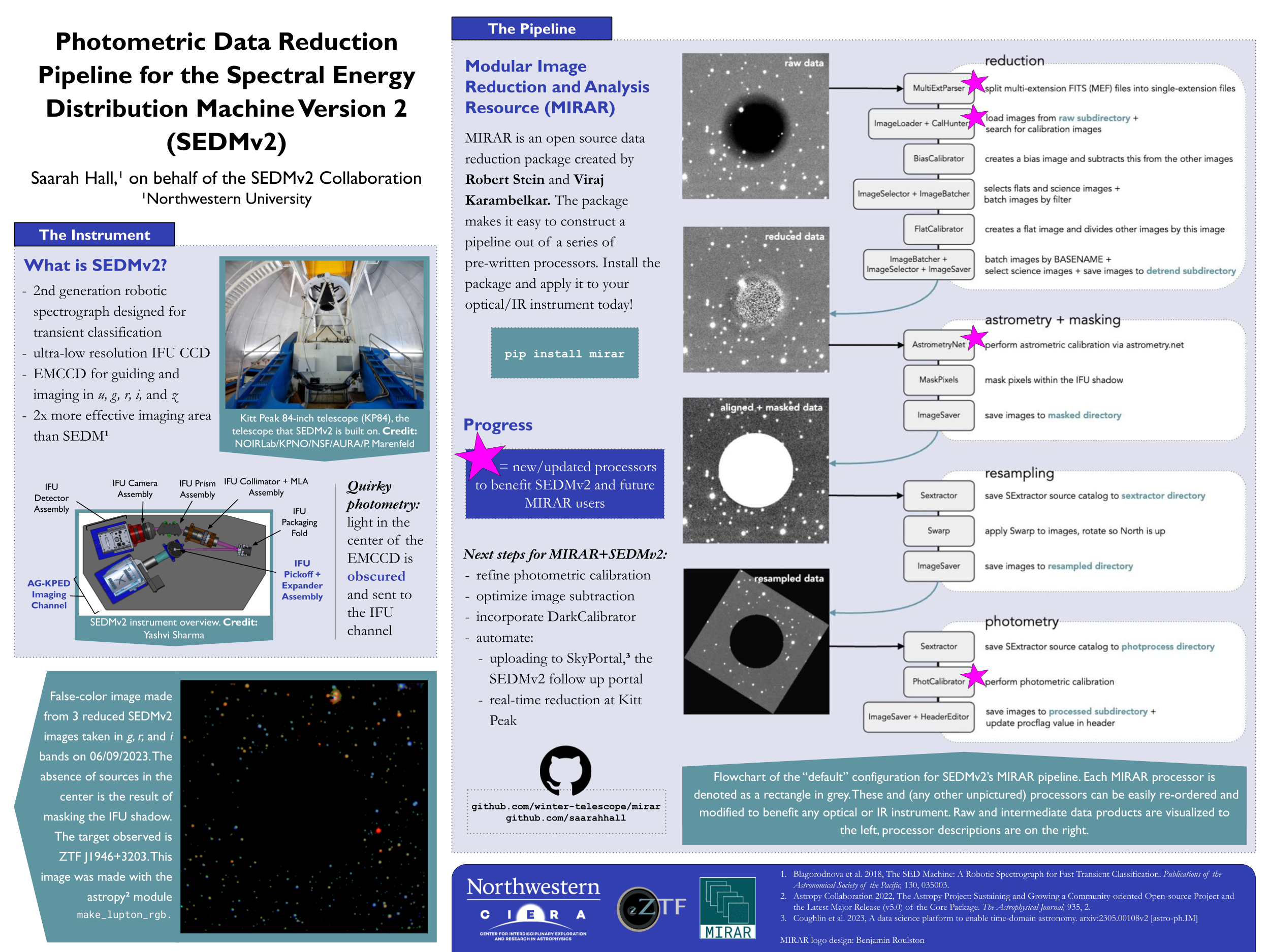

Description coming soon! While you wait, here is a poster I presented at the Transient and Variable Universe Conference at UIUC:

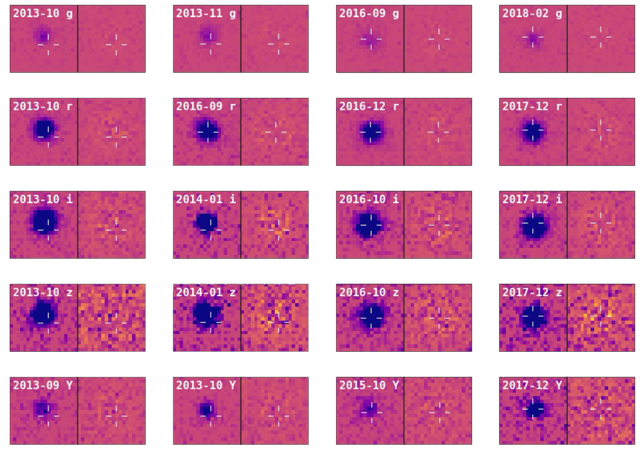

Scene Modeling Photometry on High-Proper-Motion Stars

2021-2022; UPenn; Advisor: Prof. Gary Bernstein

My experience with image subtraction software and data reduction further solidified my interest in working with astronomical images. With more technical skills under my belt, I returned to Prof. Bernstein’s group in the 2021 Fall semester to develop a model that obtains accurate measurements of fast-moving (high-proper-motion; HPM) stars present in Dark Energy Survey (DES) data. I optimized this model in the framework of scene modeling photometry (SMP), a technique for obtaining precise photometric measurements, thus building upon previous work of applying SMP to the modeling of supernovae (SNe) in DES. This SMP method is advantageous when studying moving objects because the model takes their motions into account by running on single exposures taken at different times and solving for position-related parameters and flux simultaneously. This is a critical improvement on previous DES methods since DES flux measurements are classically run on “co-add” images (many exposures stacked together), causing HPM stars to appear as smears across the image that are then mischaracterized in flux. Additionally, when this SMP tool is paired with the Dark Energy Camera’s large size and long exposures, we are able to precisely characterize HPM stars that are too faint to be detected by Gaia, a leading instrument in high-precision photometry, such as ultra-cool brown dwarfs and isolated neutron stars.

This project was the basis of my senior honors thesis. Here's a figure from my thesis:

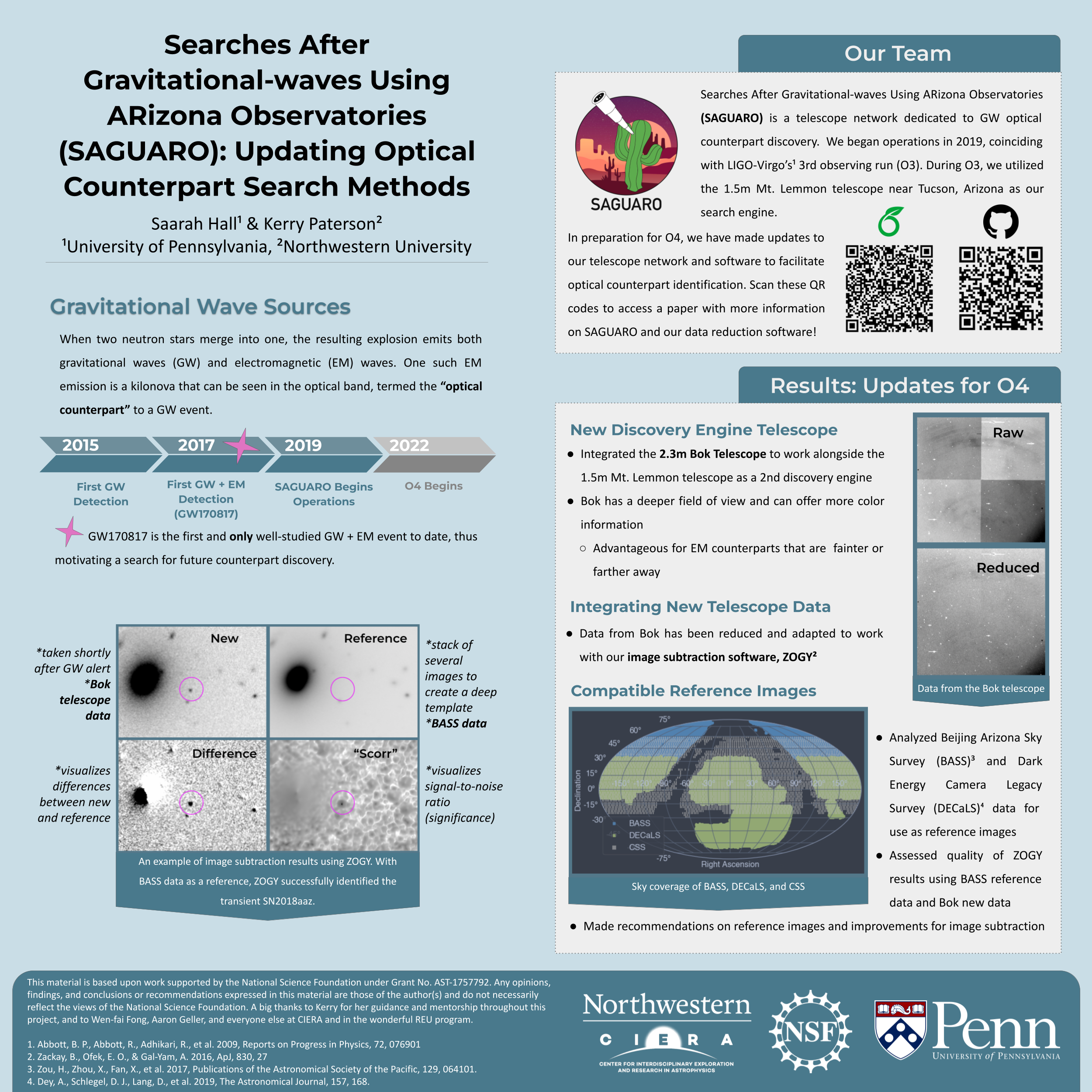

Optical Counterparts to Gravitational Wave Events

Summer 2021; Northwestern CIERA REU; Advisors: Prof. Wen-fai Fong and Dr. Kerry Paterson

With an established interest in observational astronomy, I was thrilled to join Prof. Wen-fai Fong’s group through the NSF REU at Northwestern University in the summer of 2021, developing software that would aid us in the search for electromagnetic (EM) counterparts to gravitational wave (GW) events. The EM counterparts in question, kilonovae (KNe), are rapidly dimming transients that follow the mergers of neutron stars and/or black hole, which produce gravitational waves. These elusive transients are hard to catch (their optical signals vanish within hours to a day), but the physics insights they unlock are worth the chase.

My goal was to integrate a second telescope, the 90-inch Bok telescope on Kitt Peak, into my team’s network to increase the chances of observing an EM counterpart when following up on GW detections. With this additional telescope, we are able to probe fainter and farther sources and scan a larger area of the sky within the short window of time the KN would be observable. To accomplish this, I wrote Python code to process the new telescope’s data and prepare it for the first step in our KN candidate vetting process, image subtraction. I also tested the performance of our image subtraction software to ensure that a real KN would be identified by our pipeline when analyzing data from Bok. I strengthened my Python skills by facing and conquering technical data reduction challenges: unlike my previous project, where I analyzed tidy and pre-processed DES data, I developed code that turned raw telescope images into science-ready data. By the end of the REU, I merged my code into my team’s pipeline, setting us up for success in the currently ongoing fourth observing run for GWs by LIGO.

I presented this work at the 240th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) with the iPoster above, on this research website through the REU, and I am an author on two related papers: Rastinejad et al. 2022 and Hosseinzadeh et al. 2024.

Animating Trans-Neptunian Objects

2020-2021; UPenn; Advisor: Prof. Gary Bernstein

In my first research project, I embarked on a data visualization project with the goal of creating a comprehensive “movie” about the icy bodies that orbit our Sun at distances beyond Neptune, known as Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs). At that point, the 800+ TNOs existed primarily as data in a table and had never been visualized at large scales or as an entire set. Transforming flat lines of code into animations, my work offered a never-before-seen view of TNOs moving through the solar system over thousands of years. Here is a copy of our first "movie script." And here is the movie itself (embedded below)!!

To uncover these insights, I wrote Python code that compiled thousands of Matplotlib frames into animations of TNO detections and orbits. Through this project, I realized the discovery potential of large sky surveys like the Dark Energy Survey (DES), which was the source of these TNO detections, and the importance of building fast and effective algorithms in the era of big-data astronomy. I presented this movie at a DES transients working group meeting, a collaboration-wide DES video conference, and to an audience of scientists and non-scientists alike at the conclusion of a thesis defense of the student who originally compiled this data: Pedro Bernardinelli.

This was the perfect first project for me - it was a crash course in Python data visualization (I had no coding experience at the time), and a beautiful mix of astronomy and art (Prof. Bernstein came up with the project knowing that I was also working as a video editor at the Singh Center)! If you're really interested, I documented my progress in this lab journal as part of Penn's P&A Undergraduate Summer Research Academy. (It's a bit of time capsule for what life was like in the covid-era as a newbie researcher.)